Manila, the Philippines

November 30, 2020

No pandemic could put a damper on the development of our capital city. Mayor of Manila, Yorme Isko, had kick-started his revitalization initiatives at the area around Manila City Hall before the world ground to a halt in the first quarter of 2020. While I spent months at home on self-imposed lockdown, public works in the city hardly paused.

Bonifacio Shrine / Katipunan Revolution Monument and Kartilya Park

It took Austrian influencers Mike and Nelly of Making it Happen Vlog to draw me out of the safety of my cocoon. Their coverage of the newly-facelifted Bonifacio Shrine and the surrounding Kartilya Park captured my fancy. They came for an event I could smell – the Manila Coffee Festival. I caught the tail end that fell on Bonifacio Day, the holiday of the hero commemorated by the landmark shrine of Manila.

Kapetolyo by SGD

The crumbling outhouse left to rot behind the statue of Sisa had finally been demolished and on the site sprung the glass-walled café with a pun for a name: Kapetolyo by SGD, shorthand for Sagada where their specialty coffee beans came from. The high ceiling and mood lighting looked inviting, but, honestly, Ki and I chose social distancing over our caffeine fix.

No love lost as sampler coffee flowed freely from an array of outdoor stalls. The festival showcased indigenous beans from north to south, such as Ambaguio from Nueva Vizcaya and Nayong Kalikasan from Cavite, respectively, both of which we tried.

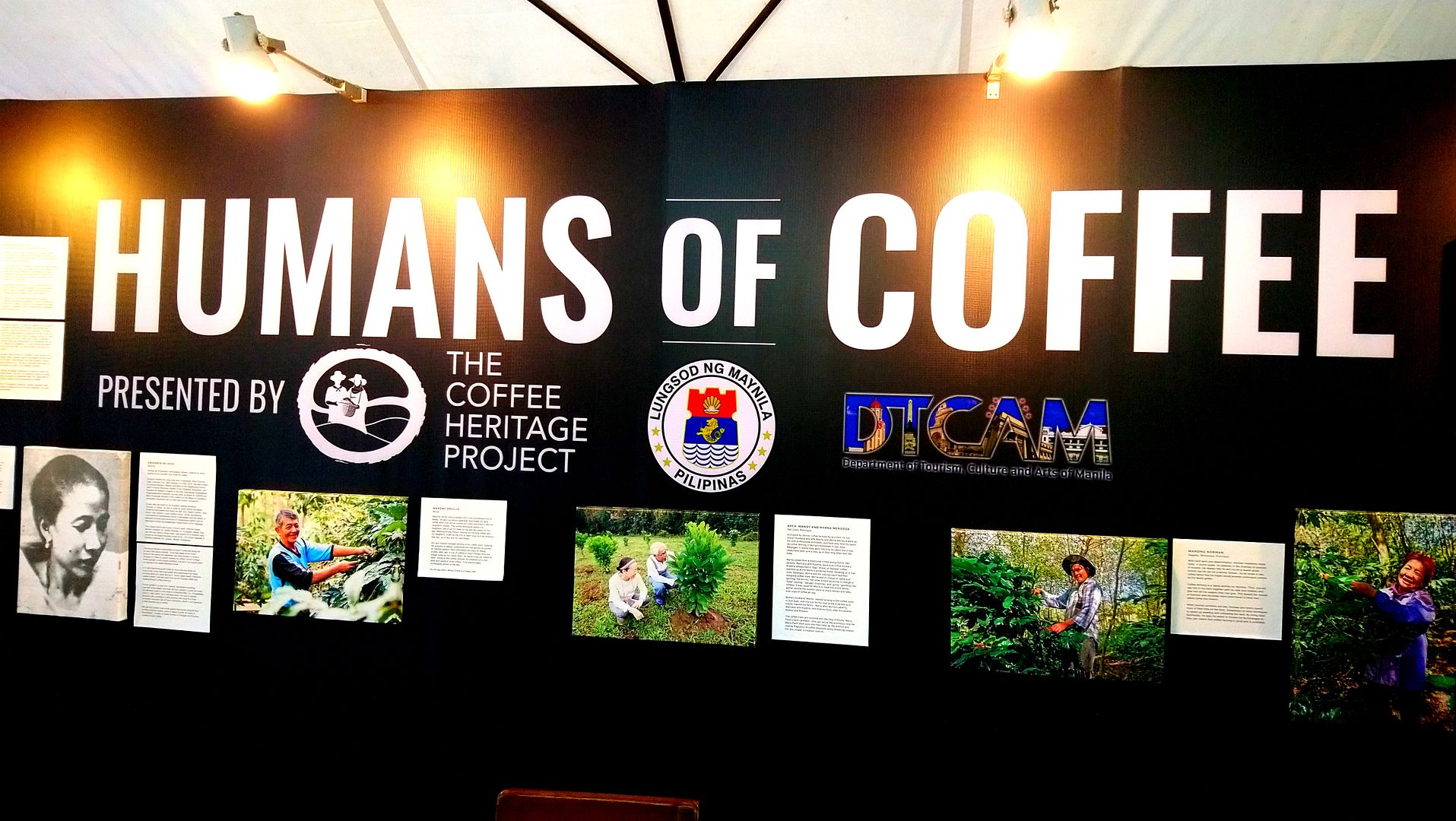

Then, we were schooled on Philippine coffee heritage by way of Humans of Coffee, an exhibition of photos and stories of personalities that figured in local coffee history and the present industry.

Fragment 22

Thus caffeinated, we explored the new and improved Kartilya Park. Our most jaw-dropping discovery was a relic of modern world history encased in glass behind the shrine. Fragment 22, a graffiti-painted piece of the Berlin Wall, was donated by the German government back in 2014, yet I had never heard of it at all. It had been exhibited at the National Museum before its debut in this public space on October 5th in the pandemic year.

The historic concrete slab was given in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the fall of the wall and the end of the Cold War. Somehow it did not feel out of place beside the memorial for Martial Law victims. The significance despite the difference in time, place, and ideologies was not lost on me.

What we came for, actually, was the newly-dressed up underpass, but not before passing by a salakot-shaped security outpost. Even an outpost did not escape gentrification.

Lagusnilad Underpass

The transformation of the formerly DDD (dark, dirty, dangerous) Lagusnilad Underpass in Lawton was well-documented in social media. Grime and graffiti had been scrubbed off, informal vendors driven away – the latter causing a kink in Yorme’s otherwise popularly-supported efforts.

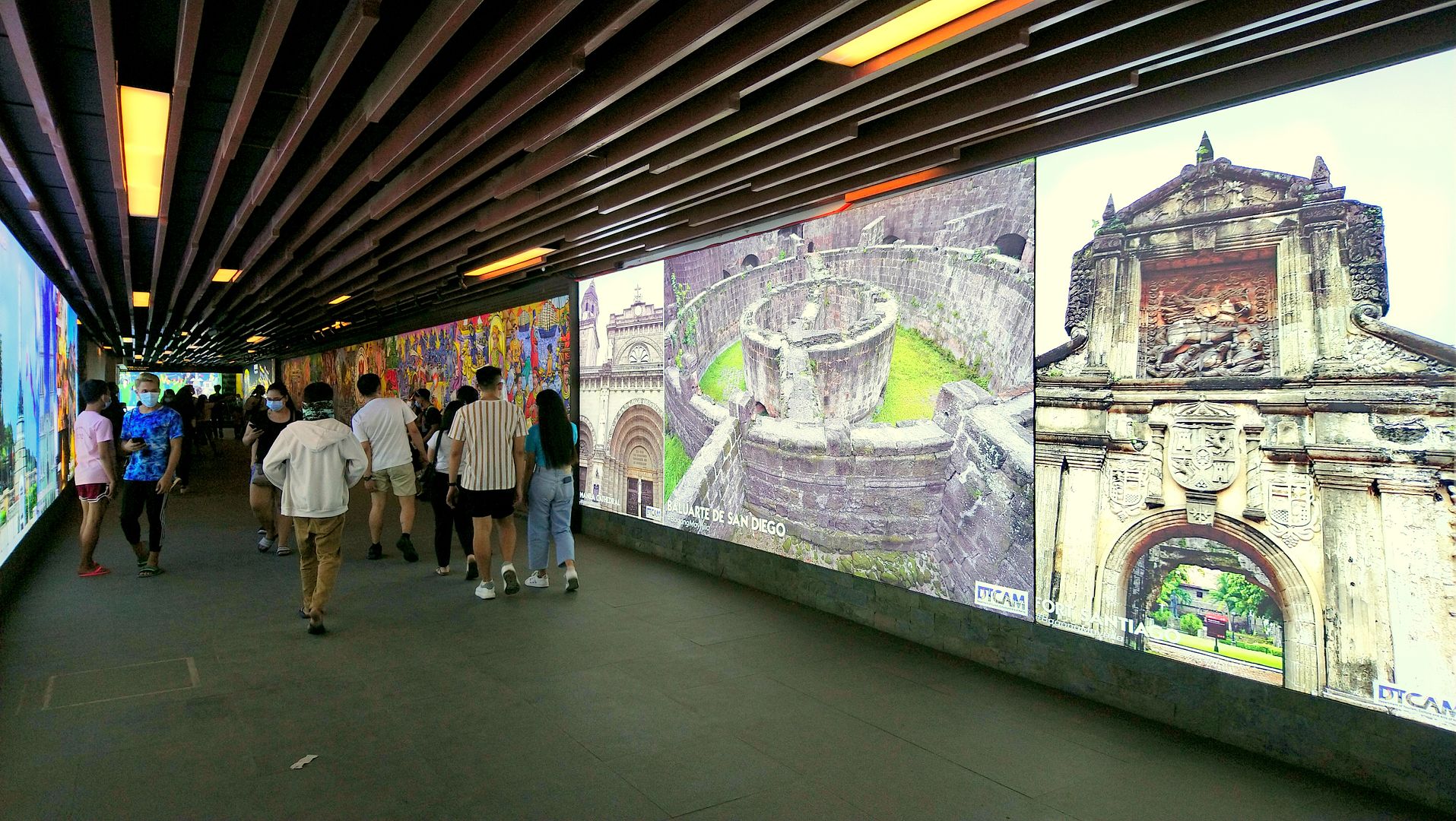

Artists from the academe were tapped to design and beautify the project. The architect hailed from the University of Santo Tomas (UST) and the muralists from the University of the Philippines (UP). Almost the entire length of the underpass walls was adorned with artwork.

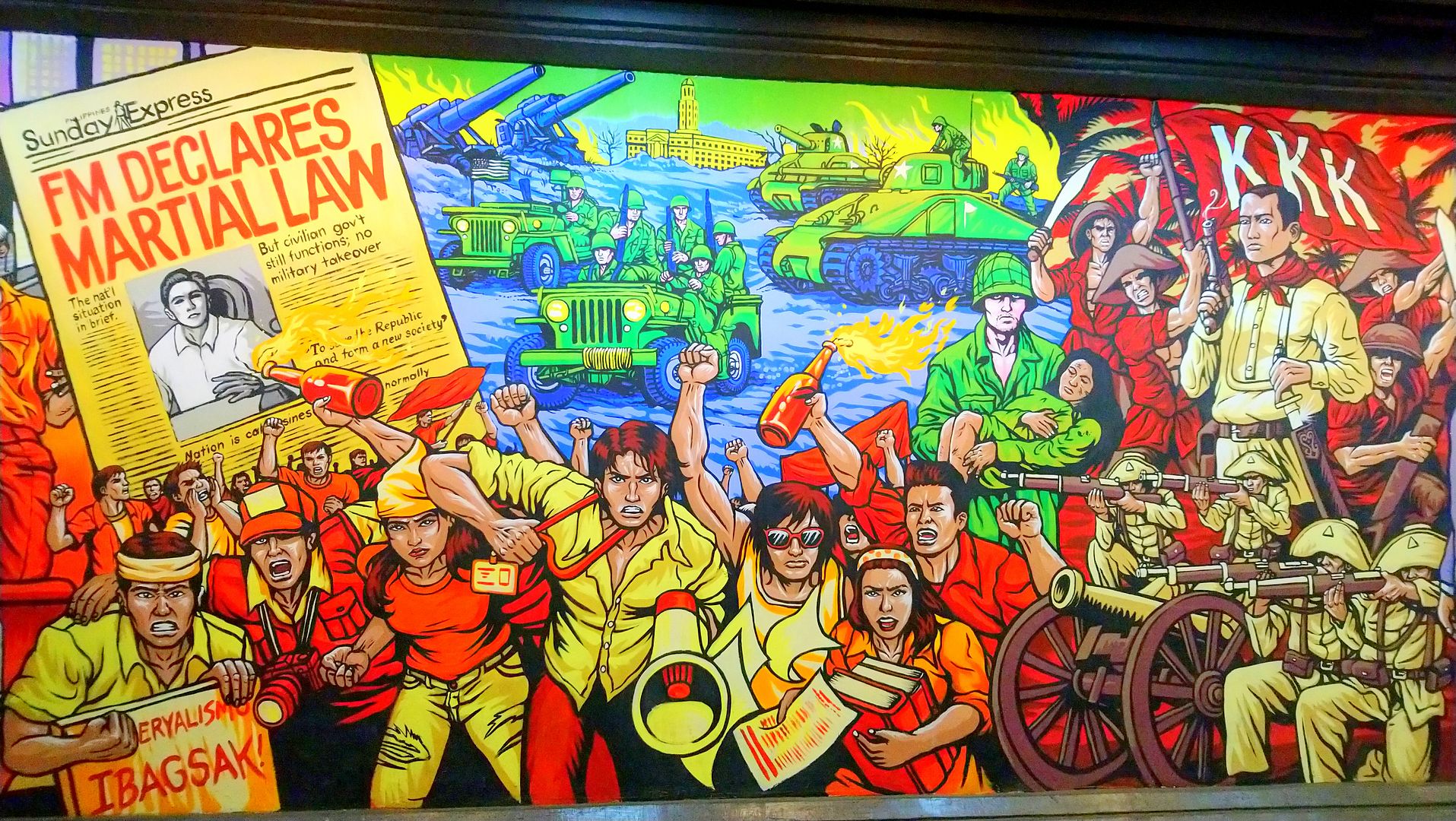

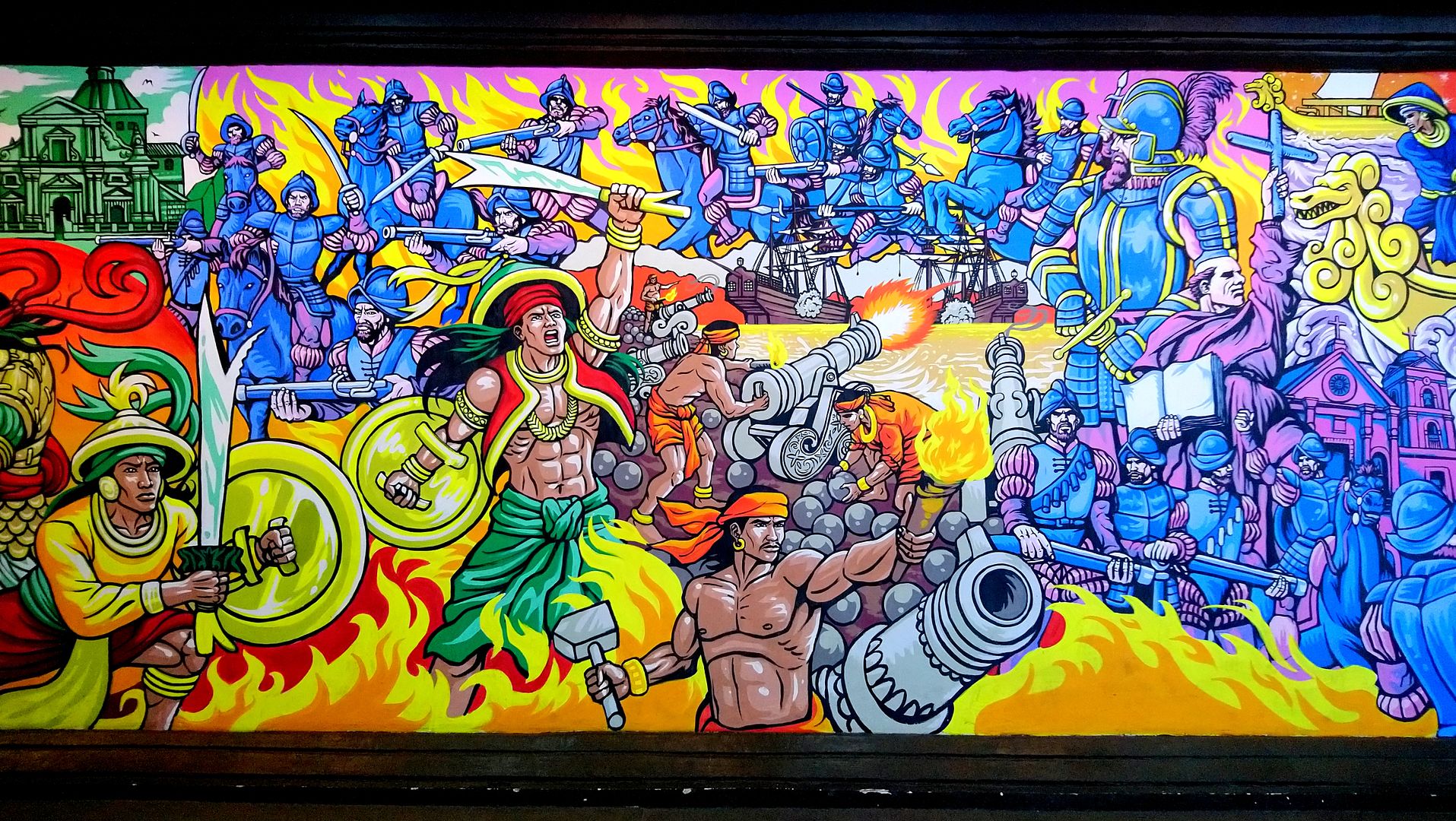

An artist collective called Gerilya – no red-tagging, please – from UP College of Fine Arts created a Botong Francisco-inspired mural that told the rich history of the Philippines in images. The centerpiece Masigasig na Maynila encompassed the pre-colonial rajah kingdoms to the present pandemic with masked medical frontliners and sought to place Manila in all those contexts. Each section representing particular historical periods was dense with imagery though not as comprehensive as it could still be.

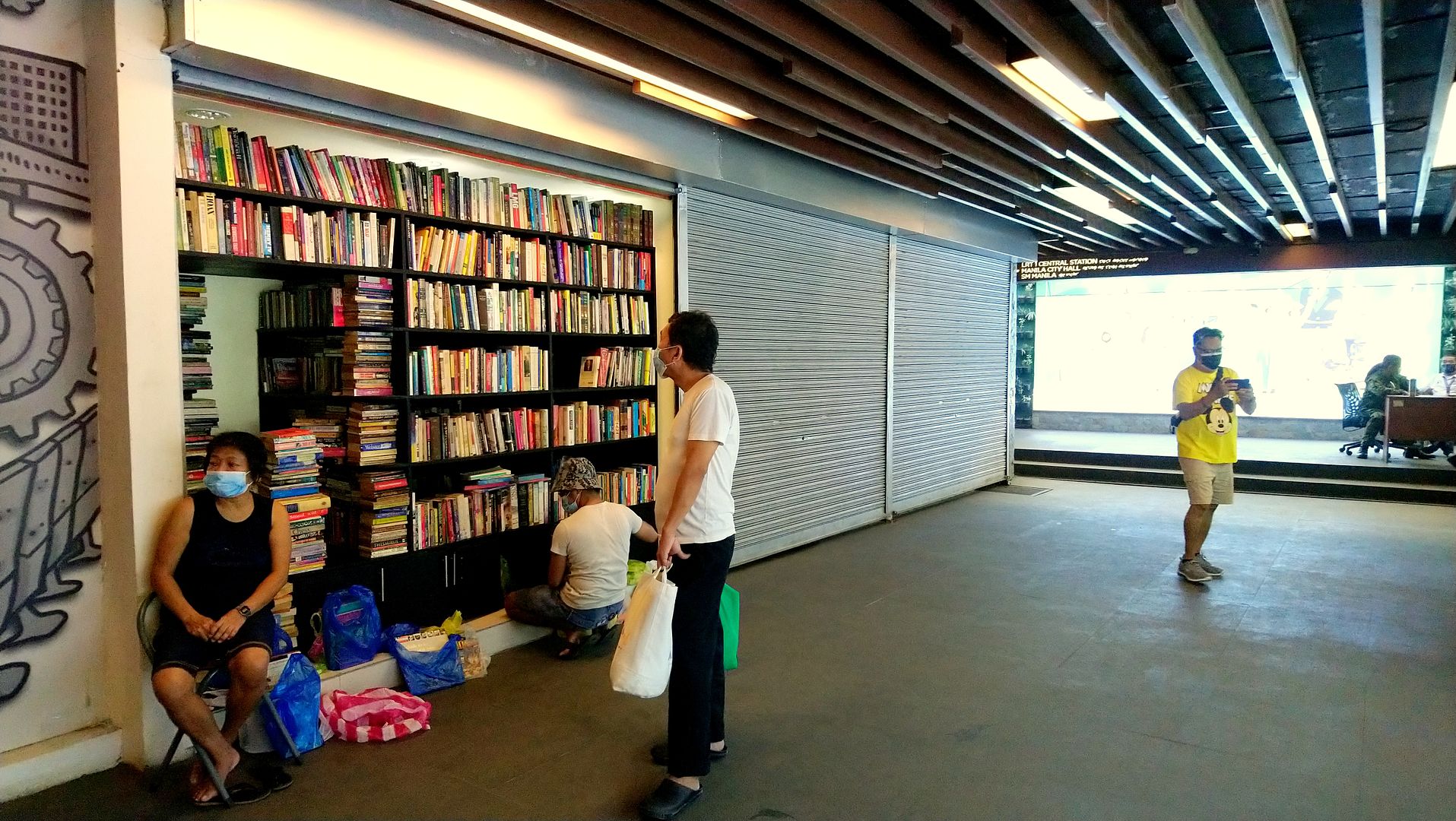

A B&W piece occupied part of the opposite wall depicting various Filipino workers from farmers to call center agents. Ki noticed that none of them wore a smile on their face. Overworked? Underpaid? Or both? Only the thrift bookstore Books from Underground among the former vendors remained in the underpass. Commercial niches beside it were still boarded up.

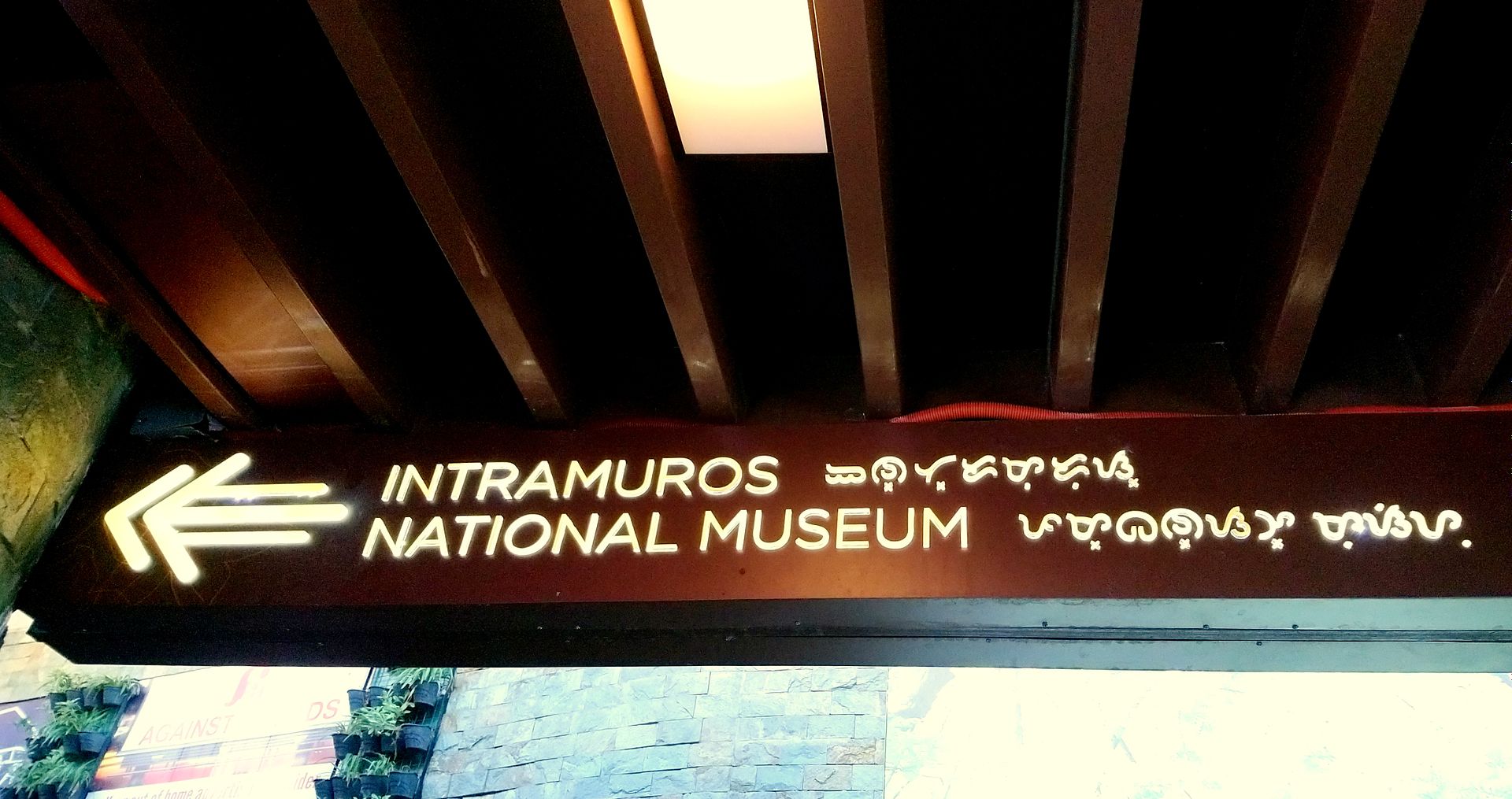

Wooden elements and LED lighting imbued the underpass with homey warmth. Directional signs, not so common in this country, had finally been installed for tourists as had backlit photographs of the city’s sightseeing sites. The use of Baybayin script in the signs was a clever touch as were the vertical hydroponic gardens at the entrances finally manned with security.

Though Lagusnilad was just one underpass connecting the Manila City Hall and Intramuros, it was an intrinsic part of a grander plan to upgrade the center of the capital to world-class quality for visitors and a dignified living space for locals.

Musical Dancing Fountain

It was nearly twilight when we emerged from the underpass. Media cameras had already been set up at Kartilya Park. Twice I was accosted by security for mindlessly wandering at the plaza in front of the shrine. It turned out the pavement was timed to be transformed into the musical dancing fountain that came on at dusk until late evening. For 15 minutes, rows of gushing fountains were choreographed to OPM (Original Pilipino Music).

The music and light show was spectacular, but a lone figure managed to steal the spotlight. A young man in katipunero garb wandered in front of the dancing fountain as if lost in both time and place. Perhaps he was the staff that Ki interviewed in his vlog earlier or he was the same guy on stilts who, minutes ago, was lip-synching to a Ronan Keating song blaring from loudspeakers. In any or both cases, Jerome Montealegre memorably capped our Bonifacio Day outing.

Thanks for reading! If you like my content, you may…

.jpg)